Healthcare Disparities occur when:

- Patients with the same healthcare issue experience different clinical outcomes because they have differences in one of the following

- Racial or ethnic group

- Religion

- Socioeconomic status

- Gender

- Sexual orientation or gender identity

- Other characteristic historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.

- Other characteristic historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.

- Different clinical outcomes occur after accounting for all other issues such as access to care, insurance status, economic status, compliance issues, etc.

The cost behind healthcare disparities

From a purely economic standpoint, healthcare disparities cost everyone money. When diving into the numbers, the costs can be staggering. In fact, a study from the International Journal of Health Services determined the medical costs of disparities in the U.S. in 2003-2006 to be $230 billion.1 Further, almost anything that raises the cost of healthcare, in general, tends to raise insurance premiums.

On a smaller scale, savings can be realized at the state level if disparities were reduced or eliminated. For example, North Carolina could save $225 million/year if both racial & economic disparities in diabetes prevalence were eliminated.2

Healthcare disparities cost lives

Beyond the monetary facts, what is most noteworthy is that healthcare disparities cost lives. And the best way for us to determine the number of lives and years lost from varying diseases due to healthcare disparities is by using census data.

When looking at only cancer, stroke, diabetes, and heart disease together, each year, over 37,000 lives are lost and over 4,000,000 years of Black, Hispanic and Native American life are lost.3,4,5,6,7

Healthcare disparities have existed in the U.S. medical system since its inception in the mid-19th century, due to segregation at hospitals by race, ethnicity & socioeconomic factors.8 Fortunately, desegregation came about in the 1960’s. This was accomplished due to financial incentives, because Medicare refused payment to segregated institutions.9 Since then, numerous studies show ongoing healthcare disparities in a variety of clinical areas, including heart disease.10,11 Unfortunately, the general medical community has ignored these studies, claiming that the results must be due to differences in economics, insurance status, access, etc. However, the studies have taken all these factors into account and controlled for them.

Study highlights disparities in treatment

Fortunately, in 1999, two things happened. The first, was a very special study published in the New England Journal of Medicine looking at how race and gender affected how doctors chose treatment for heart disease for their patients. 12

The study had actors read from a script describing their history and symptoms. All actors had the same medical history, social background, and insurance. The only difference among the actors was their race and/or gender. It showed that whites and males had cardiac catheterization interventions most often while blacks and females most often were given watchful waiting. The only difference was the physicians’ preconceived biases. It was impossible to state there was any other reason for these decision outcomes.

The second event was that Ted Koppel chose to air this study on Nightline. The show caused a public outcry that reached Capitol Hill. An investigation was initiated, and the Congressional report, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care”13 was published. This stated the following findings:

- 2-1: Racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare occur in the context of broader historic and contemporary social and economic inequality, and evidence of persistent racial and ethnic discrimination in many sectors of American life.13

- 3-1: Many sources – including health systems, healthcare providers, patients, and utilization managers – may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare.13

- 4-1: Bias, stereotyping, prejudice, and clinical uncertainty on the part of healthcare providers may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare.13

Despite the widely read publication, resulting legislation regarding cultural competency in healthcare and numerous ongoing studies of healthcare disparities, most of the disparate outcomes have failed to improve over the past 20 years.

Areas where disparities have failed to improve significantly, include but are not limited to the following conditions:14

- Death from heart disease and stroke

- Preterm births

- Infant deaths

- Uncontrolled hypertension and potentially preventable hospitalizations for diabetes, hypertension

- Congestive heart failure

- Angina

- Asthma

- Dehydration

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Urinary infections

Issues at the heart of healthcare disparities

The cause for the initial and ongoing disparities are twofold. One issue is the role Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) play. Studies have demonstrated the percentage that different factors contribute to a person’s overall health status:15

- Behavioral patterns: 40%

- Genetic predisposition: 30%

- Social circumstances: 15%

- Healthcare: 10%

- Environmental exposure: 5%

These numbers show that social circumstances and environmental exposure together, count twice as much as the quality of healthcare received in determining one’s health. These two together are the SDoH. They include the following:

- Economic stability (employment, income, debt, expenses, medical bills)

- Neighborhood/environment (housing, safety, transportation, parks, walkability, playgrounds)

- Education (literacy, language, early childhood & higher education, vocational training)

- Food (hunger, access to healthy and/or affordable options)

- Community/Social context (social integration, support systems, discrimination, community engagement)

Patients historically linked to discrimination or exclusion characteristically have increased issues with the SDoH. However, one thing 2020 has shown us, is that racial and ethnic bias is still alive and active in the U.S. This bias is often hidden, or implicit, unknown to the person in whom it resides. As shown by Project Implicit,16 it’s nearly impossible to reside in the U.S. today without at least some minimum of hidden bias deep in our self-consciousness, no matter what our background. It exists in the healthcare system and is the second reason for the ongoing disparities.

Overcoming Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) Issues

While the disparities may seem insurmountable, here are two great success stories that show how healthcare disparities can be overcome by actively creating programs that address the SDoH issues.

First, let’s look at the city of Lowell, Massachusetts. It has the second largest Cambodian population in U.S., as well as a large populations of immigrants from Burma, Thailand, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Somalia, Bhutan, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Iraq. Of the population, thirty percent do not speak any English, while several have poor health literacy, transportation and financial issues.

Further complicating matters for the large Cambodian population was that many had been impacted by the horrible crimes against humanity of the Khmer Rouge regime. The regime is most famous for its Tuol Sleng prison, where more than 12,000 Cambodians were tortured and executed. Because of their deplorable actions, the regime engrained a deep distrust for anyone who looked like a government official, including doctors in white coats.

To aid in overcoming mistrust, area providers established the Metta Health Center to better connect with the community population. They employed 40 community health workers, who spoke 28 languages and specialized in Eastern approaches to treatment, including meditation, acupuncture and massage. Further, their doctors did not wear ties or white lab coats. By taking these small steps and adopting a culturally competent approach, the Center’s infection rate of Hepatitis B in Cambodians was cut by 50 percent, while morbidity rates declined by 30 percent.

How Youth Uprising is transforming their community

Youth UpRising, in East Oakland, California is another example of how a community can activey address SDoH issues. An organization founded on the belief that if they provide youth with relevant services, programs, and opportunities they will become contributors to a healthy, thriving community.

Their programs help prevent youth violence and help transform the lives of area youth already involved in violence. Their health and wellness programs provide holistic accessible care in a community setting. With primary health and mental health services offered onsite. Other free services include, case management, a computer lab, multimedia room, performing arts amphitheater, visual art & film production, sports and physical fitness and café. By creating a fostering and caring environment, they have aided in the wellness of more than 13,000 area youth. Further, they help more than 400 youths find employment annually, and have collected more than 850 firearms at sponsored Buy Back events.

Closing thoughts

A final thing to consider when thinking about ways to address healthcare disparities is to follow the money. Remember that SDoH has twice the power to affect the outcomes of health versus the quality of their care.

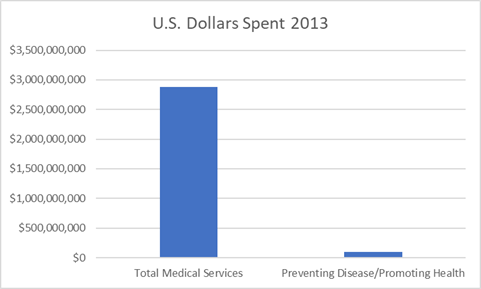

Below is a graph showing what the U.S. spends on medical services versus preventing disease/promoting health through social services.

Perhaps we, as a country, need to reconsider what is important to finance in order to improve our overall health and well-being.

If you are concerned about healthcare disparities, there are several things you can do. The first is to educate yourself. Numerous articles exist on this topic and are easily accessible. Next, if you belong to one of the groups affected by the disparities, learn to become an advocate for yourself and your family. If you are not a member of one of those groups, become an advocate for them. Speak out when you see something questionable occurring. Finally, become politically involved.

References

1 LaVeist Thomas, Gaskin Darrell J, Richard Patrick. Estimating the Economic Burden of Racial Health Inequalities in the United States. International Journal of Health Services. 2011;41(2):231–38

2 Buescher PA, Whitmire JT, Pullen-Smith B. Medical care costs for diabetes associated with health disparities among adult Medicaid enrollees in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2010 Jul-Aug;71(4):319–24.

3 CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 2013 (LCWK1. Deaths, percent of total deaths, and death rates for the 15 leading causes of death in 5-year age groups, by race and sex: United States, 2013).

4 Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2013. National vital statistics reports; vol 65 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016.

5 Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Bastian BA. Deaths: Final data for 2013. National vital statistics reports; vol 64 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2016.

6 American Fact Finder. 2013 population estimates. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, age, race and Hispanic origin for the United States and States: April1, 2010 to July 1, 2013. United States Census Bureau. National characteristics: vintage 2014. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/national/asrh/2014/.

7 Trend tables. Health, United States, 2015.Table 18 (page 1 of 4). Years of potential life lost before age 75 for selected causes of death, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, selected years 1980–2014. U.S. Census Bureau, National Vital Statistics System (NVSS).http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2015.htm#018.

8 Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. 101-8

9 Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.104-5

10 Leaverton PE, Feinleib M, Thom T. Coronary heart disease mortality rates in United States blacks, 1968–1978: interstate variation. Am Heart J. 1984;108(3 Pt 2):732–7.

11 Sempos C, Cooper R, Kovar MG, McMillen M. Divergence of the recent trends in coronary mortality for the four major race-sex groups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;78(11):1422-1427.

12 Schulman K.A., Berlin J.A., Harless W. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340(8):618–626.

13 Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

14 CDC/US HHS. CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report-United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Supplement / Vol. 62 / No. 3. November 22, 2013.

15 Schroder, SA (2007). We Can Do Better-Improving the Health of the American People. NEJM, 357:1221-8. https://www.projectimplicit.net/index.html

16 KFF analysis of National Health Expenditure (NHE) data Get the data PNG. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/u-s-spending-healthcare-changed-time/#item-nhe-trends_total-national-health-expenditures-us-billions-1970-2018

17 Wang, F., Wang, J. & Huang, Y. Health expenditures spent for prevention, economic performance, and social welfare. Health Econ Rev 6, 45 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-016-0119-1